Death By GPS

Editor’s Note: Many lessons can be learned by studying the failures of people before us. In this article we look at the many takeaways that could have saved the souls of many people, including Sanchez’s 6 year-old-boy.

- Plan on alternate forms of communication. Consider HAM Radio, or Satellite Phone.

- Know how to navigate with old technology, such as basic Land Navigation skills with a compass, the stars, or primitive compass techniques.

- Learn some basic Survival Skills, or Desert Survival Skills before entering the desert.

- Bring Water!

Hopefully this article, and a little pre-planning, will make you realized how important these skills are for SHTF… even if SHTF only happens to you…

This article was originally published on JANUARY 30, 2011 at SacBee.com, By Tom Knudson.

As tourists flock to Death Valley, technology leads some astray.

Five harrowing days after becoming stuck on a remote backcountry road in Death Valley National Park in August 2009, Alicia Sanchez lay down next to her Jeep Cherokee and prepared to die.

Then she heard a voice.

“I called as I approached, asking if she was okay,” wrote Ranger Amber Nattrass in a park report. “She was waving frantically and screaming, ‘My baby is dead, my baby is dead.’ ”

In the SUV, Nattrass found Sanchez’s lifeless 6-year-old son Carlos on the front seat. “She told me they walked 10 miles but couldn’t find any help (and) had run out of water and had been drinking their own urine,” Nattrass wrote.

“She turned down a wrong road,” Nattrass said in a recent interview. “She said she was following her GPS unit.”

Danger has long stalked those who venture into California’s desert in the heat of summer. But today, with more people pouring into the region, technology and tragedy are mixing in new and unexpected ways.

“It’s what I’m beginning to call death by GPS,” said Death Valley wilderness coordinator Charlie Callagan. “People are renting vehicles with GPS and they have no idea how it works and they are willing to trust the GPS to lead them into the middle of nowhere.”

The number of people visiting Death Valley in the summer, when temperatures often exceed 120 degrees, has soared from 97,000 in 1985 to 257,500 in 2009. That pattern holds at Joshua Tree as well, which recorded 128,000 visitors in the summer of 1988. Last year: 230,000.

With another potentially deadly summer season approaching, Death Valley managers now are adding heat danger warnings to dozens of new wayside exhibits and working with technology companies to remove closed and hazardous roads from GPS units. They also have posted warnings on the park’s website, telling visitors not to rely on cell phones or GPS units.

“It’s important for people to know that only a tiny portion of Death Valley has cell phone reception,” search and rescue coordinator Micah Alley wrote in an e-mail. “GPS units are not only fallible but send people across the desert where no road exists.”

Over the past 15 years, at least a dozen people have died in Death Valley from heat-related illnesses, and many others have come close. Another hiker vanished last June in Joshua Tree National Park. His body has not yet been found.

These are not just stories of unimaginable suffering. They are reminders that even with a growing suite of digital devices at our side, technology cannot guarantee survival in the wild. Worse, it is giving many a false sense of security and luring some into danger and death.

Technology, of course, is not the only denominator to those disasters. Others include poor planning, faulty judgment, bad luck and the lemming-like rush of visitors to Death Valley in the summer, many of them unfamiliar with the danger – making heat-related illness and fatalities nearly as predictable as the searing temperatures.

“We expect it every summer,” said Callagan. “It’s actually more unusual to end up without any deaths. It seems like we have one or two every summer.”

Danger soars in summer

Much of the year, Death Valley is actually more lovely than life-threatening. That is especially true in the spring, when silver ribbons of water splash down canyon walls and dozens of species of wildflowers, from Mojave asters to Indian paintbrush, bloom in technicolor abandon.

But summer is a different story. The park map is dotted with names suggesting the danger, such as Deadman Pass, Coffin Peak, the Funeral Mountains and the Devil’s Golf Course.

“It’s hard to appreciate what 120 degrees is like and how quickly you can get into trouble if you are exposed to it for any length of time,” said Scott Wanek, chief ranger for the Pacific West Region of the National Park Service.

No disaster makes that point more tragically than the disappearance of four German tourists – two adults and two boys, ages 3 and 10 – whose rental van became stuck on a remote road in Death Valley during an intense heat wave in July 1996 and who were never heard from again.

Their fate remained a mystery until November 2009, when Tom Mahood, a retired engineer and search-and-rescue volunteer, and a colleague, Les Walker, discovered human bones, the woman’s wallet and other items in an isolated corner of the park near Butte Valley.

“It’s very scenic and remote but a really awful place to die,” said Mahood on a six-mile hike earlier this month through the rugged backcountry of Joshua Tree National Park, where he was searching for Atlanta businessman Bill Ewasko, who vanished last June.

“People don’t just disappear,” said Mahood, who spent countless hours searching for the Germans long after others had given up. “They have to be somewhere.”

The German tourists “made some classic errors,” said Callagan, the Death Valley wilderness coordinator. “They had no business being where they were in a van, alone, in the summer. They didn’t have a good map. The road systems out in Butte Valley are confusing. They were traveling in the summer, unprepared. Did they have 10 gallons of water? No. They had very little.”

“Death Valley is a dramatic place,” Callagan added. “But it’s not something to be toyed with.”

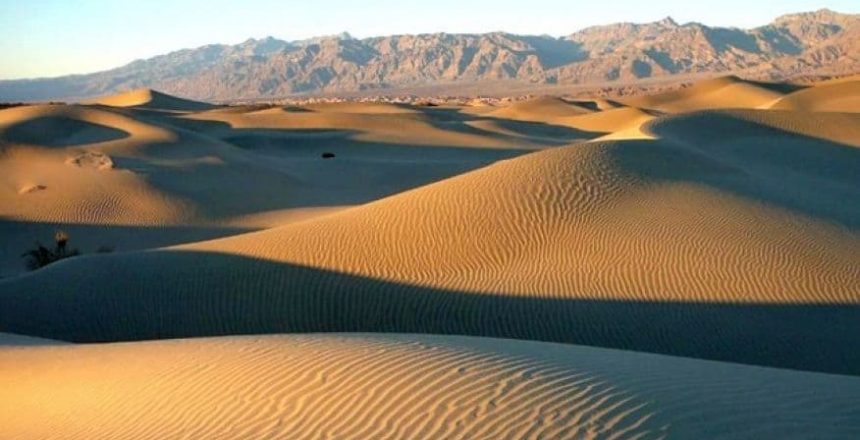

The largest park in America, outside Alaska, Death Valley is a vast panorama of latte-colored mountains, Sahara-like dunes and a white-as-table-salt valley floor that is home to the lowest, driest and hottest spot in North America – Badwater Basin – at 282 feet below sea level.

“It feels like you are standing in front of an open oven,” said Ranger Nattrass, who has spent the past four summers in the park. “There are times when you stand outside and the heat can take your breath away.”

Not all GPS units reliable

The park spells out the dangers of heat and dehydration in special warnings distributed to visitors each summer. It is installing 49 new wayside exhibits around the park that will include heat and desert survival warnings.

“We want people to enjoy their wild lands,” said Alley, the search and rescue coordinator. “But we want them to have the tools and information to do it safely.”

Increasingly, park rangers say tourists are being led into danger by technology, especially satellite-based GPS units designed to guide them to unfamiliar destinations along a network of roads in a navigation database.

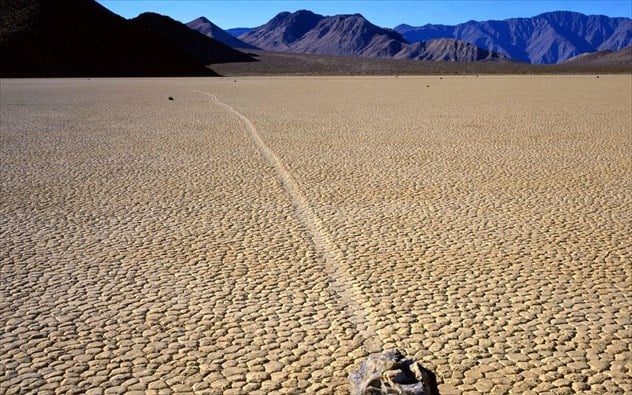

In Death Valley, many roads shown on some GPS systems are no longer passable. Some have been officially closed. Others are simply too rough for most vehicles and pose serious danger.

“People are so reliant on their GPS that they fail to look out the windshield and make wise decisions based on what they’re seeing,” said Alley.

One case happened last summer, when visitors arriving from the west on Highway 190 told their GPS to take them to Scotty’s Castle, a popular tourist destination at the north end of the park, which is easily accessible by paved road.

Instead, the unit directed them over an unpaved, winding, washboard road toward Saline Valley, where they turned right onto an even rougher four-wheel-drive road and became stuck near a remote abandoned mine site called Lippincott.

“People don’t realize that if they tell the unit to find the shortest route to somewhere, it’s not necessarily finding the shortest, safe, paved route,” Callagan said.

“One of the healthier ones walked out, 20 to 25 miles, and made contact with one of our rangers,” he added. “Everybody survived, but they weren’t in great shape.”

‘Just turn around’

Six-year-old Carlos Sanchez was not so lucky. He died in the 115-degree heat after a Jeep his mother, Alicia, was driving became stuck on an isolated road in the southwest corner of the park in 2009. And according to Amber Nattrass – the ranger who found them – GPS played a role in leading the mother astray.

“She was following a GPS unit,” Natrass said.

Sanchez was trying to drive into Death Valley from the south via an unpaved route along the valley floor called the Harry Wade Road. Instead, she ended up on a dead-end backcountry road, which she followed for more than 20 miles along the south side of the Owlshead Mountains.

“The road is very rough. It’s a hard drive,” said Nattrass. “There was probably a point where she said, ‘Oh my God, I don’t know where I am. I’m going to keep going because I think I’m going the right direction.’

“A lot of people don’t realize you should just turn around and go back the way you came,” she said. “We see that a lot here.”

Near where the road ends, Nattrass followed the tire tracks that turned onto “a closed road in the wilderness area going over several small bushes and rocks lined along the road to designate closure,” her report says.

And it was down that road – on Aug. 6, 2009 – that Nattrass spotted the Jeep stuck up to its axles in the sand with SOS spelled in medical tape on the windshield. Alicia, then 28, a nurse from Las Vegas, was lying next to it in the shade, distraught over the death of her son and so dehydrated she had been drinking her own urine.

“She came running toward me and collapsed in my arms. Her lips were very dry and chapped with bleeding blisters and her tongue appeared to be swollen with very little saliva formation,” Nattrass wrote in her report. “I walked over to the Jeep and looked inside. I saw a boy slumped in the front seat with obvious signs of death.

“She told me the last time they ate a meal was on Friday, July 31. Sanchez told me the two had attempted to eat a Pop Tart on Sunday 8/2 but it was ‘too dry to swallow.’

“Sanchez told me that her son had become delirious and confused before he died, telling her he was ‘speaking to my grandfather in heaven’ and that ‘a woman is reading a story to me.’

“Both her and her son believed they were going to die. She told me at one time he prayed out loud, ‘Oh God, take me now.’ ”

“Whether or not her GPS unit was showing that road, or she just saw evidence of a road, I can’t tell you for sure,” Nattrass said. “A map in that case may have been a lifesaver for them.”

Callagan said the wilderness road where the boy died showed up on some GPS units but does not know if Sanchez’s GPS was one of them. “Some of the databases on the GPS units are showing old roads that haven’t been open in 40 years,” he said.

Lately, Callagan has been working with technology companies to remove closed and hazardous roads from their navigation databases – but with only partial success.

“I’m pulling my hair,” he said. “I was never able to reach a single human with Google Earth Maps. But in their system, they have a way you can let them know something is wrong. And over the course of a year, I was able to get their maps updated.”

Things went more smoothly with TomTom, a major manufacturer of GPS units for cars. “I had a representative right here. He was real professional. I was able to sit down and say, ‘Nope, that doesn’t exist,’ ” Callagan said.

That representative was Matthew Rinaldi, a geographic sourcing analyst for the company. “I knew there were issues in Death Valley, consumer-wide, for all GPS devices, not just TomTom,” Rinaldi said.

In all, Rinaldi said he made adjustments to 185 Death Valley road segments in the company’s navigation database and removed about 50 altogether.

But other GPS databases remain uncorrected, meaning future travelers remain at risk.

More reliable, say search and rescue professionals, are a good map, a compass and, in case of trouble, plenty of water. And for those venturing off-road, they strongly advise carrying personal locator beacons or similar devices that send a signal via satellite, advising others of your location and notifying authorities if you need help.

“Had any of these poor souls had them – the Germans or Sanchez – tragedy could have been averted,” said Mahood, the search and rescue volunteer.

1 thought on “Death By GPS – Lessons and Tragedies”

Darwinism. Sad, brutal, Darwinism.

Comments are closed.